From the Letters of Note Blog

Getting Star Trek on the air was impossible

In November of 1966, two months after the first Star Trek series premièred in the U.S., science fiction author Isaac Asimov wrote an article for TV Guide in which he complained about the numerous scientific inaccuracies found in science fiction TV shows of the day — Star Trek included. That show's creator, Gene Roddenberry, didn't take kindly to the jab, and immediately wrote to Asimov with a polite but stern response that also went some way to explaining the difficulties of bringing such a show to the screen. His letter can be read below.

Asimov apologised, and in fact became a good friend of Roddenberry's and an advisor to the show. Also below is a fascinating exchange of theirs that took place some months later, just as a problem arose relating to the relationship between Captain Kirk and Spock — a potentially damaging problem that Asimov helped to solve.

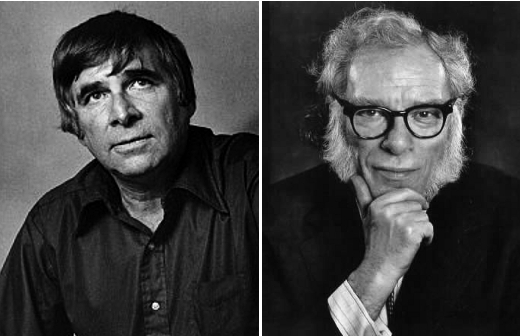

(Source: Star Trek Creator: The Authorized Biography of Gene Roddenberry; Images of Gene Roddenberry & Isaac Asimov via here & here.)

29 November, 1966

Dear Isaac:

Sorry I had to address it in this round-about way since I did not have your address and Harlan Ellison, who might have supplied it, is working a final draft for us and is already a week late and I don't want to take his attention away from it for even a moment. On second thought, I believe he is a month or two late.

Wanted to comment on your TV Guide article, "What Are A Few Galaxies Among Friends?"

Enjoyed it as I enjoy all your writing. And it will serve as a handy reference to those of our Star Trek writers who do not have a SF background. Although, to be perfectly honest, those with SF background and experience tend to make the same mistakes. I've found that the best SF writing is no guarantee of science accuracy.

A person should get his facts straight when writing anything. So, as much as I enjoyed your article, I am haunted by this need to write you with the suggestion that some of your facts were not straight. And, just as a writer writing about science should know what a galaxy is, a writer writing about television has an obligation to acquaint himself with pertinent aspects of that field. In all friendliness, and with sincere thanks for the hundreds of wonderful hours of reading you have given me, it does seem to me that your article overlooked entirely the practical, factual and scientific problems involved in getting a television show on the air and keeping it there. Television deserved much criticism, not just SF alone but all of it, but that criticism should be aimed, not shot-gunned. For example, Star Trek almost did not get on the air because it refused to do a juvenile science fiction, because it refused to put a "Lassie" aboard the space ship, and because it insisted on hiring Dick Matheson, Harlan Ellison, A.E. Van Vogt, Phil Farmer, and so on. (Not all of these came through since TV scripting is a highly difficult specialty, but many of them did.)

In the specific comment you made about Star Trek, the mysterious cloud being "one-half light-year outside the Galaxy," I agree certainly that this was stated badly, but on the other hand, it got past a Rand Corporation physicist who is hired by us to review all of our stories and scripts, and further, got past Kellum deForest Research who is also hired to do the same job.

And, needless to say, it got past me.

We do spend several hundred dollars a week to guarantee scientific accuracy. And several hundred more dollars a week to guarantee other forms of accuracy, logical progressions, etc. Before going into production we made up a "Writer's Guide" covering many of these things and we send out new pages, amendments, lists of terminology, excerpts of science articles, etc., to our writers continually. And to our directors. And specific science information to our actors depending on the job they portray. For example, we are presently accumulating a file on space medicine for De Forest Kelly who plays the ship's surgeon aboard the USS Enterprise. William Shatner, playing Captain James Kirk, and Leonard Nimoy, playing Mr. Spock, spend much of their free time reading articles, clippings, SF stories, and other material we send them.

Despite all of this we do make mistakes and will probably continue to make them. The reason—Thursday has an annoying way of coming up once a week, and five working days an episode is a crushing burden, an impossible one. The wonder of it is not that we make mistakes, but that we are able to turn out once a week science fiction which is (if we are to believe SF writers and fans who are writing us in increasing numbers) the first true SF series ever made on television. We like to think this is what we are trying to do, and trying with considerable pride. And I suppose with considerable touchiness when we believe we are criticized unfairly or as in the case of your article, damned with faint praise. Quoting Ted Sturgeon who made his first script attempt with us (and now seems firmly established as a contributor to good television), getting Star Trek on the air was impossible, putting out a program like this on a TV budget is impossible, reaching the necessary mass audience without alienating the select SF audience is impossible, not succumbing to network pressure to "juvenilize" the show is impossible, keeping it on the air is impossible. We've done all of these things. Perhaps someone else could have done it better, but no one else did.

Again, if we are to believe our letters (now mounting into the thousands), we are reaching a vast number of people who never before understood SF or enjoyed it. We are, in fact, making fans—making future purchasers of SF magazines and novels, making future box office receipts for SF films. We are, I sincerely hope, making new purchasers of "The Foundation" novels, "I, Robot," "The Rest of the Robots," and other of your excellent work. We, and I personally, in our own way and beset with the strange problems of this mass communications media, work as proudly and as hard as any other SF writer in this land.

If mention was to be made of SF in television, we deserved much better. And, as much as I admire you in your work, I felt an obligation to reply.

And, I believe, the public deserves a more definitive article on all this. Perhaps TV Guide is not the marketplace for it, but if you ever care to throw the Asimov mind and wit toward a definitive TV piece, please count on us for facts, figures, sample budgets, practical production examples, and samples of scripts from rough story to the usual multitude of drafts, samples of mass media "pressure," and whatever else we can give you.

Sincerely yours,

Gene Roddenberry

-----------------------

[Seven months later...]

June, 1967

Dear Isaac,

Wish you were out here.

I would dearly love to discuss with you a problem about the show and the format. It concerns Captain James Kirk and of course the actor who plays that role, William Shatner. Bill is a fine actor, has been in leads on Broadway, has done excellent motion pictures, is generally rated as fine an actor as we have in this country. But we're not getting the use of him that we should and it is not his fault. It's easy to give good situations and good lines to Spock. And to a lesser extent the same rule is true of the irascible Dr. McCoy. I guess it's something like doing a scene with several businessmen in a room with an Eskimo. The interesting and amusing situations, the clever lines, would tend to go to the Eskimo. Or in our case, the Eskimos.

And yet Star Trek needs a strong lead, an Earth lead. Without diminishing the importance of the secondary continuing characters. But the problem we generally find is this—if we play Kirk as a true ship commander, strong and hard, devoted to career and service, it too often makes him seem unlikable. On the other hand, if we play him too warm-hearted, friendly and so on, the attitude often is "how did a guy like that get to be a ship commander?" Sort of a damned if he does and damned if he doesn't situation. Actually, although it is missed by the general audience, it is Kirk's fine handling of a most difficult role that permits Spock and the others to come off as well as they do. But Kirk does deserve more and so does the actor who plays him. I am in something of a quandary about it.

Got any ideas?

Gene

-----------------------

Gene,

In some way, this is the example of the general problems of first banana/second banana. The star has to be a well-rounded individual but the supporting player can be a "humorous" man in the Elizabethan sense. He can specialize. Since his role is smaller and less important, he can be made highly seasoned, and his peculiarities and humors can easily win a wide following simply because they are so marked and even predictable. The top banana is disregarded simply because he carries the show and must do many things in many ways. The proof of the pudding is that it is rare for a second banana to be able to support a show in his old character if he keeps that character. There are exceptions. Gomer Pyle made it as Gomer Pyle (and acquired a second banana of his own in the person of the sergeant.)

Undoubtedly, it is hard on the top banana (who like all actors has a healthy streak of insecurity and needs vocal and constant reassurance from the audience) to not feel drowned out. Everybody in the show knows exactly how important and how good Mr. Shatner is, and so do all the actors, including even Mr. Shatner. Still, when the fan letters go to Mr. Nimoy and articles like mine concentrate on him, one can't help feeling unappreciated.

What to do? Well, let me think about it and write another letter in a few days. I don't know that I'll have any magic solutions, but you know, some vagrant thought of mine might spark some thought in you and who knows.

Isaac

[A few weeks later...]

Gene,

I promised to get back to you with my thoughts on the question of Mr. Shatner and the dilemma of playing against such a fad-character as "Mr. Spock."

The more I think about it, the more I think the problem is psychological. That is, Star Trek is successful, and I think it will prove easier to get a renewal for the third year than was the case for the second. The chief practical reason for its success Mr. Spock. The excellence of the stories and the acting brings in the intelligent audience (who aren't enough in numbers, alas, to affect the ratings appreciably) but Mr. Spock brings in the "teenage vote" which does send the ratings over the top. Therefore, nothing can or should be done about that. (Besides, Mr. Spock is a wonderful character and I would be most reluctant to change him in any way.)

The problem, then, is how to convince the world, and Mr. Shatner, that Mr. Shatner is the lead.

It seems to me that the only thing one can do is lead from strength. Mr. Shatner is a versatile and talented actor and perhaps this should be made plain by giving him a chance at a variety of roles. In other words, an effort should be made to work up story plots in which Mr. Shatner has an opportunity to put on disguises or take over roles of unusual nature. A bravura display of his versatility would be impressive indeed and would probably make the whole deal a great deal more fun for Mr. Shatner. (He might also consider that a display of virtuosity would stand him in great stead when the time—the sad time—came that Star Trek had finished its run and he must look elsewhere.)

Then, too, it might be well to unify the team of Kirk and Spock a bit, by having them actively meet various menaces together with one saving the life of the other on occasion. The idea of this would be to get people to think of Kirk when they think of Spock.

And, finally, the most important suggestion of all—ignore this letter, unless it happens to make sense to you.

Isaac

-----------------------

Isaac,

Your comments on Shatner and Spock were most interesting and I have passed them on to Gene Coon and others. We've followed one idea immediately, that of having Spock save his Captain's life, in an up-coming show. I will follow your advice about having them much more a team, standing more closely together. As for having Shatner play more varied roles, we have been looking in that direction and will continue to do so.

But I think the most important comment is that of keeping them a close team. Shatner will come off ahead by showing he is fond of the teenage idol; Spock will do well by displaying great loyalty to his Captain.

In a way it will give us one lead, the team.

Gene

No comments:

Post a Comment